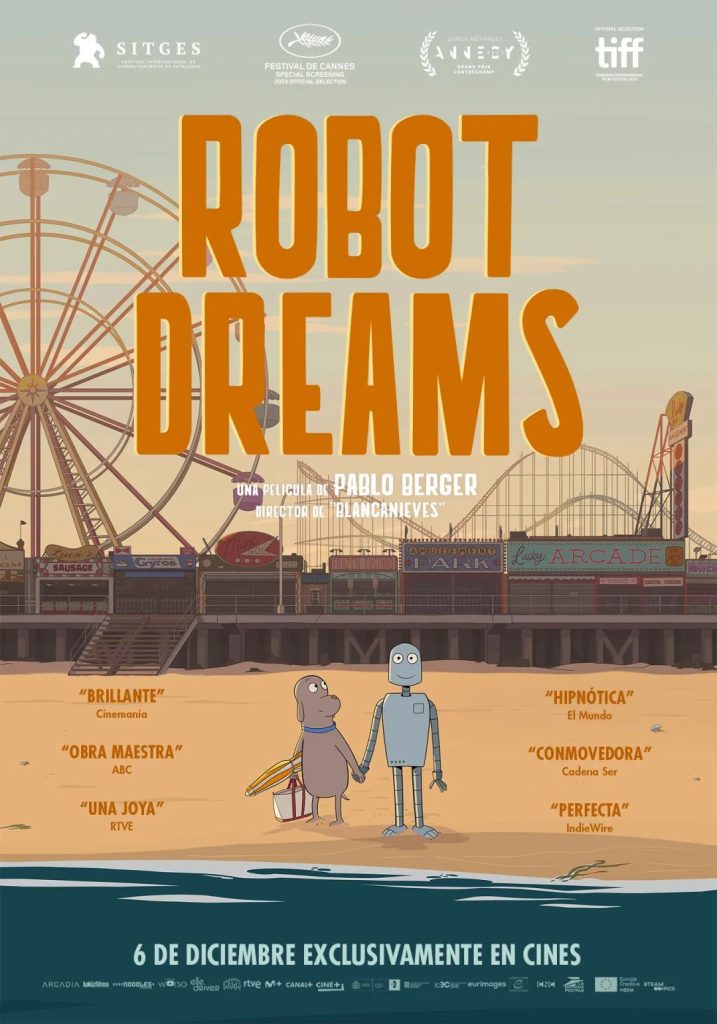

This year’s Oscar nominations for Best Animated Feature include a film that stands alongside works like “The Boy and the Heron,” “Elemental,” and “Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse.” Despite initially flying under the radar, it has gained significant acclaim in later stages, becoming a dark horse with “immense emotional impact.”

Indeed, “Robot Dreams” is an animated film that appears to be technically simple. The entire film has no dialogue, and the protagonists are not humans but a lonely dog and a robot it loses. Its visual style is reminiscent of children’s books we used to read when we were young.

A dog without friends saw an advertisement one day and ordered a robot. The robot accompanied it through a short period of happiness, but everything ended completely after a seaside vacation. The dog did not protect the robot, and due to mechanical drowning and uncontrollable factors, the robot was abandoned by the sea. The forced separation returned the dog to a lonely life, occasionally reminiscing about its once best friend, while the robot endured harsh springs, summers, autumns, and winters on the beach, dreaming of its best friend.

The story is so simple, yet even if the audience are adults, they still seem unable to face and handle such heartbreak. After a small sweet gift, the entire animation is obsessed with depicting intense anticipation and bitter loss. The beautiful old days become sharp hidden weapons in the gaps of life, peeling away the sunshine that might be encountered tomorrow.

The robot does not have life characteristics; its pure emotions are more like a program setting, but this has also moved many viewers. From the first moment they met, the robot and the dog were in an unequal relationship. The robot had an emotional comfort function for the dog; all its perceptions and experiences of this world were related to the dog. This point is repeatedly confirmed in dreams: everything and every spectacle leads to the dog’s home.

That piece of music with “commitment” meaning is simply the heart of the robot; it is through melody that we perceive the heartbeat of a lifeless machine. However, the fear and suspicion of losing a friend expressed by the robot in dreams transcend this setting.

Undoubtedly, dreams are where all romance in this animation comes from. In dreams, the robot seems more like a truly autonomous being, but being trapped in a shell on the beach creates an absolute contrast between reality and dreams.

The rotation of seasons leaves marks in dreams; parallel worlds create insurmountable distances matched by repeated missed opportunities—just one step away from returning to the past.

In fact, the dog is closer to an ordinary person in real life—a lonely bachelor lost in city life, confined to monotonous routines 24 hours a day. The dog does not have a continuous self but has a real need for happiness. This need manifests in various choices after losing contact with the robot. The dog sought new friends and entered new relationships but ended up alone due to indecision and lack of contribution.

The dog needs an object for unilateral salvation just like people spiritually and mentally empty in urban life can only describe and create material things to fill their void but cannot grow independently.

Meanwhile, even without many opportunities for parting by death or separation, loneliness and distance can affect friendships. In both the dog and robot’s relationship, we see those fragile details within relationships and fundamental reasons why happiness is fleeting: sometimes we voluntarily enter cages; sometimes it’s because of cages themselves—even if we truly have friendship or love—it’s customized within cages.

Ultimately, “Robot Dreams” succeeds by creating sensory experiences that touch souls, allowing audiences to feel charm through visual storytelling.

This is actually Spanish director Pablo Berger’s first animated film; his previous works varied greatly in style—especially outstanding was “Snow White,” a true silent film. Similarly without dialogue but adapted from Sara Varon’s comic book—this animation focuses on a more modern era set in 1980s New York City.

At that time New York was both cultural & economic capital—you had to be there physically to understand what was happening culturally—but now everything is decentralized—the center of world culture can be anywhere—from small towns getting information no different than being in New York City itself.

Initially conceived with only two protagonists—the robot & dog—New York wasn’t central—but during production major changes included adding many New York elements giving city itself chance for cross-temporal self-expression opportunities—they watched many ’80s films like Martin Scorsese’s “After Hours,” Woody Allen’s “Hannah And Her Sisters,” some Jim Jarmusch films—and lesser-known Susan Seidelman’s “Desperately Seeking Susan.”

Photographic works also served as references—Martha Cooper being an excellent photographer who genuinely captured lives of hip-hop artists during ’70s & ’80s—animation style stylized using these symbolic components pieced together.

Meanwhile aiming for distinct compositions—everything must be clear like comic books so viewers hardly feel camera movement blurring visuals—as director said—in this film everything is focus point.

New York revives within work—not just city atmosphere—but narrative & rhythm atmosphere too—with cool jazz bringing sense traveling through time—smarter settings include music choices—a pop music medley representing New York—they searched many iconic pop songs undoubtedly Earth Wind & Fire’s “September” became main theme song—a source emotional moments throughout golden times.

“Robot Dreams” tells story about friendship memory learning how say goodbye—those no longer appearing lives those once loved you or were loved by you—and times spent together taking long time digest properly store deep hearts.